Recap of the Gateway Long-Term Care Policy Conference’s Panel Discussion – Research to Practice: Informing Long-Term Care Policy through Economic Evidence

Written by: Maya Fransz-Myers

Published on: Nov 29, 2023

On November 7-8, 2023, the Gateway hosted our Long-Term Care (LTC) Policy Conference in Washington, D.C., with over 50 attendees including researchers, policymakers, and practitioners.

The scientific committee selected fifteen papers to be presented over the two-day event. From well-being to quality of care, each of these presentations, along with two panels of policymakers, practitioners, and academic experts, came together with the goal of connecting LTC research to a broader understanding of how policies can be applied to improve effectiveness, efficiency, and outcomes for care recipients and their families.

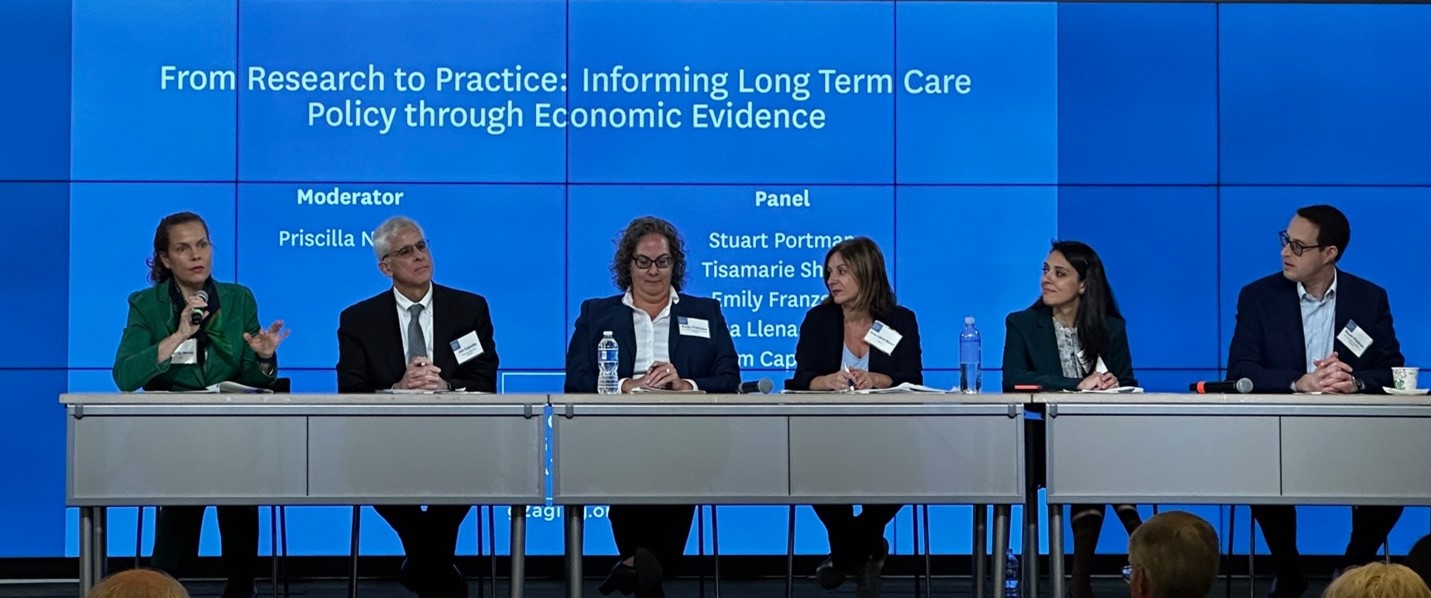

Our first panel discussed the state of LTC policy in the U.S. and around the globe. Priscilla Novak, Program Officer at the U.S. National Institute on Aging (NIA), moderated the conversation with several LTC policymaking experts: Jim Capretta, Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute; Emily Franzosa, Health and Aging Policy Fellow at the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging; Ana Llena-Nozal, Senior Economist at the OECD; Tisamarie Sherry, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in charge of the Office of Behavioral Health, Disability, and Aging Policy; and Stuart Portman, Senior Health Policy Advisor on the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance.

We highlight key takeaways from the panel discussion without attribution.

1. From left to right: Priscilla Novak, Jim Capretta, Emily Franzosa, Ana Llena-Nozal, Tisamarie Sherry, and Stuart Portman.

The U.S. Long-Term Care System

The primary payer for LTC in the U.S. is Medicaid, a means-tested, public health insurance program administered at the state level and financed jointly by the federal and state government. Given its reliance on federal funding, Congress’ power of the purse lends itself to some influence over state programs. For example, states must cover certain populations (e.g., Supplemental Security Income recipients) and benefits (e.g., nursing facility care) to receive funding.

Congress has used this power, but have they been successful? Research shows that older adults prefer to age in place, whether in their home or community, unless a more intensive level of care is needed. And yet, institutional care is one of the only required LTC benefits under Medicaid. The panel discussed Congress’ position as the deciding body that authorizes funds for Medicaid expansions. With the main LTC benefit being institutional care, policy at the federal level is not focused on the care people want – home-based care. Because federal mandates are just that – federal – Congress faces a significant barrier to action. It is difficult to sell a federal mandate to states with Medicaid programs of varying generosity. Differing views, motivations, and varying powers within the legislative process cause policymakers to take issues in smaller bites, resulting in less systemic change.

State Flexibility and Alternative LTC Policy Designs Under Medicaid

Aside from the few federal requirements, the rest is essentially left to the state (see the Gateway’s new LTC Policy Explorer comparing state systems). Panelists shared lessons learned about LTC service delivery given the flexibility granted to state governments. While not mandatory, uptake in options to expand Medicaid home-and community-based services (HCBS) have nevertheless increased dramatically, with all states operating at least one HCBS waiver, and the percent of total Medicaid spending for HCBS increasing as well. Sometimes, the ability to tailor to state-specific needs can be easier than a one-size-fits-all solution.

In contrast, state flexibilities can also lead to unfortunate limitations. Around 800,000 people across the U.S. are on waitlists for HCBS – a direct result of a state’s power to cap the number of people served under certain programs.

The Cost of Long-Term Care

Cost must also be considered when evaluating or expanding the system. It’s well established that the delivery of HCBS is less expensive than nursing facility care on a per person basis, but a lower per person cost does not always mean a lower total cost. Since many people prefer to remain in the community, expanding HCBS could prove more costly in the long run by increasing demand for government supported services as people with care needs substitute away from unpaid care from family and friends.

Many intrastate inequities in LTC services provided by Medicaid require additional funds to alleviate. Even the most innovative states are struggling with coverage gaps because of high costs, waitlists, and worker shortages, and cutting costs could exacerbate these issues.

The Home Care Workforce

Turning to the supply side of the care conversation, home care workers across the country face low wages for difficult job demands, with many referring to it as “low-skilled,” when it is anything but. It is essential to consider the worker when addressing cost efficiency and care effectiveness, said a panelist. Paying care workers a living wage benefits the worker, care recipient, and our communities through increased consumer spending, job availability, and reduced reliance on public funding, but paying higher wages has the potential to substantially increase costs of operating HCBS systems.

Many caregivers are not paid at all. Unpaid family caregiving has historically been the common alternative to the high cost for public or private LTC services. Panelists urged the audience to consider the cost to families when they do not have access to caregiving support they need. When someone steps into the role of a caregiver, not only do they take on additional responsibilities, but in some cases, reduce or forgo their paid employment, substantially impacting the future well-being of the caregivers’ families and their care recipients.

Long-Term Care in the Global Context

The U.S. does not face this alone. Panelists shared how other countries similarly struggle to balance conflicting motivations. Tensions between generosity and high cost have emerged in Germany’s insurance-based system, which has had to consistently raise premiums to remain sustainable. On the other hand, many countries are implementing efficiencies such as a single point-of-entry and universal needs assessment – efforts recently agreed upon in Costa Rica. Looking at the experiences of other countries can inform policy alternatives for states and the federal government (see the Gateway’s new LTC Policy Explorer comparing country systems).

Looking to the Future

While the LTC community faces significant challenges, there are efforts being made to create more equitable and sustainable systems. In our next blog, we will highlight important takeaways from the conference and perspectives on future directions for LTC policy and research.

Our sincere thanks to all presenters, panelists, moderators, and others who attended the conference this past week. Your contributions fostered important discussions on LTC policy research and enabled further collaboration between the scientific community and the future of LTC policymaking.

- Maya Fransz-Myers is a project administrator at the University of Southern California